Human Rights in Eritrea

From the last week of June until mid-July, PEN Eritrea has been collaborating with artist and activist Gianluca Costantini to highlight the cases of forgotten Eritrean journalists. In his Human Rights in Eritrea series, the artist has produced 15 illustrations of the jailed journalists.

A faculty of Bologna School of Fine Arts and this year’s recipient of Human Rights Award from Amnesty International (Italy), Gianluca’s artistic engagement spans more than 25 years. He regularly collaborates with rights organizations such as ActionAid, Amnesty International, Cesvi, ARCI, Oxfam, among others. PEN Eritrea’s Abraham T. Zere has interviewed the artist regarding the joint campaign, his activism, and the role of an artist in times of crisis.

How did you get into activism?

In the first 10 years of my artistic career, I had mainly focused on classic art. Then I mostly dealt with aesthetics and the comic aspects of it. As my reference was literature, particularly poems, my work had been shaped by Romantic period artists. But in the last 15 years I moved to realistic drawing. My drawings are more essential, simple lines, but they have the touch of calligraphy. Slowly, but eventually, partly thanks to the influence of some leading artists, my work has dramatically shifted. Among artists that left big influence on me are the photographer Ernst Friedrich, who was active during 1st World War. Others are Raymond Pettibon, William Kentridge, and artists I had the chance to meet and work with such as Aleksandar Zograf and Ai Weiwei. With the latter I did a collaboration.

Now, with changing technology and access, my work/activism mainly concentrates on social network sites. Thanks to the great spread and sharing nature of social network sites, I use the platforms to reach wider audience. My work on Twittter, often reaches about a million impressions per month. That is the drive behind my passion now as I got the opportunity and the platform to communicate messages of people who otherwise could not speak or be heard for different reasons.

Can you tell me little about the practical works such as which parts do you use hands and which parts computer? How long on average does one illustration needs you to complete?

It depends on the period and the kind of work. For example, for the Eritrean jailed journalists, I did it digitally; as I wanted to deliver quickly. I could do them on paper but takes longer time than I take about 30 minutes digitally. The most time-consuming aspect of it is research about the subjects and finding appropriate quotes to describe each subject.

How familiar were you with Eritrea before starting to collaborate with PEN Eritrea? For example, did you know Eritrea was Italy’s colony or else Italy has been one of the first countries for most refugees from Africa who cross through the Mediterranean Sea?

Not really, that’s why I got passionate on the series. I enjoy the challenges of working on unfamiliar subjects or out of my comfort zone. Yes, of course I did know that Eritrea was an Italian colony and I’m aware of the situation of Mediterranean Sea. I’ve just finished a new book which is going to be released in October about Libya; one story in the book is about Eritrean girl who crosses the Mediterranean Sea. It is based on the work of a prominent Italian journalist, Francesca Mannocchi, who had widely covered the arduous journey.

From the drawings of Eritrean journalists, I can tell you study each journalist critically and I was pleasantly amazed how catching and defining lines you were coming up for each. Can you tell me little about the process you do on studying your subjects?

Drawing about Eritrea was not easy: there are very few photos of prisoners, old pictures and not of good quality. To overcome this, I studied many features of Eritrean faces, then I tried reproducing them with very few lines, but at the same time I had to be extra cautious to be accurate. It is crucial to have simple drawings that attempt to project bigger cause.

Now that you are familiar with the incarcerated Eritrean journalists and have read at least biographical sketch of each of them. Does any journalist stand out on your memory, if so who and why?

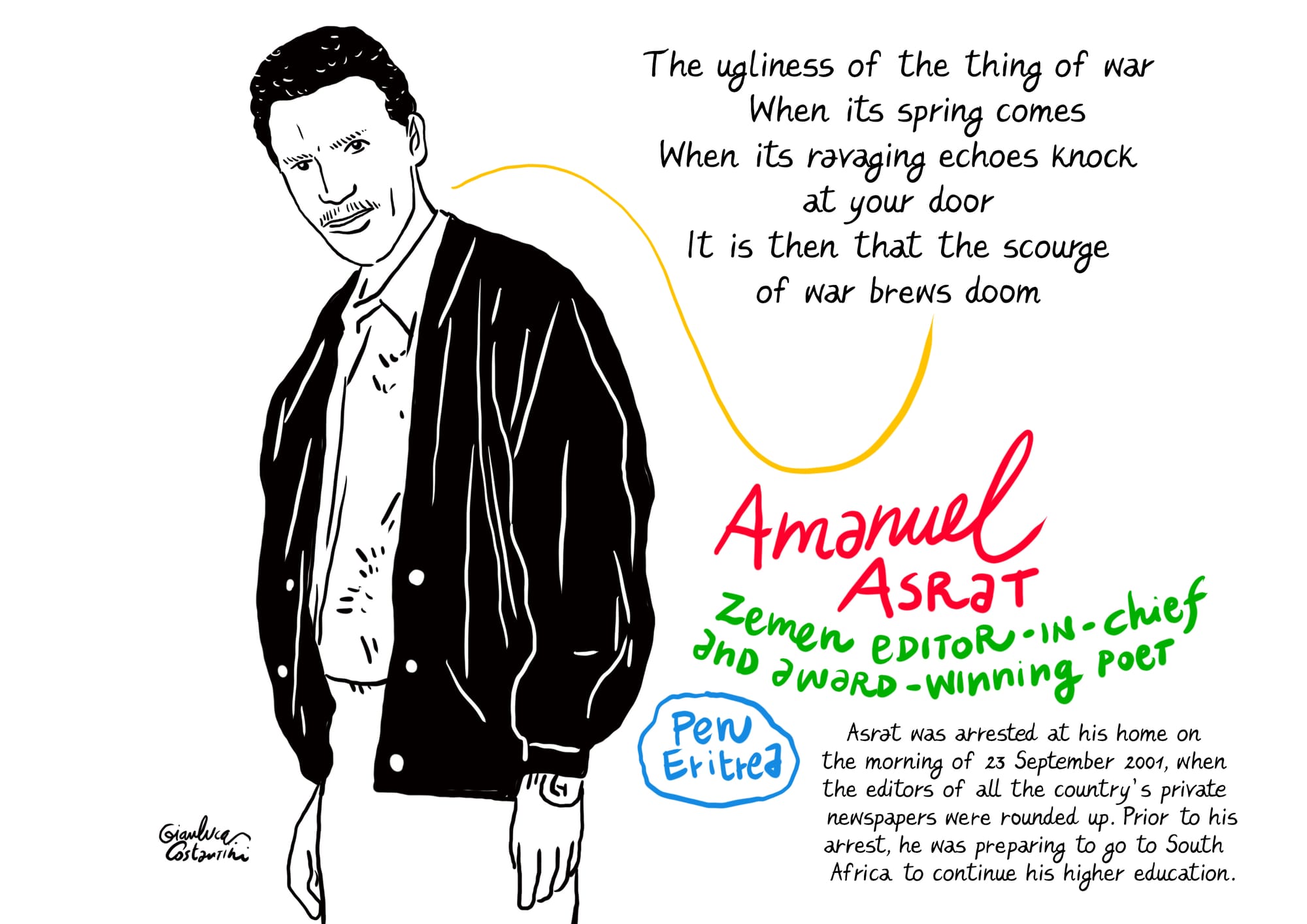

Amanuel Asrat’s words profoundly moved me, his poem is just beautiful; Dawit Isaak is fascinating. But of course, I reflected on each of them equally. It is horrible to think and imagine what has happened to the Eritrean journalists and writers.

You have experienced some censorship in Turkey and expectedly your cartoons and drawings would anger authorities on the opposite end. Have you ever faced any personal threats? Or do you receive hate messages?

I have been labeled a terrorist by Turkish government after the failed coup in 2016. They blocked my social media accounts and my website in Turkey’s territory. This happened following my drawings of the fights in a border town called Cizre.

Apart from that, occasionally, I receive hate messages if I publish art works that deal with Italian situation. But, it is very rare to be personally attacked and targeted if you work on international issues.

Starting from the so called most democratic countries in the West to others that are following the footsteps, the world is descending into extreme far-right ideology and increasingly becoming intolerant. What do you think is the role of artists like yourself in such crucial juncture?

I believe an artist has the responsibility to take stand and denounce such trends with the medium s/he has. Unfortunately, very few of us are doing it openly, even though art could be the strongest voice against radical ideology and injustice. I encourage young artists to join the cause and be part of the struggle. For these who concentrate on landscape and portrait paintings, I believe, the world is fine for them as it is now.

By nature of your work, you are positioned on the side of the oppressed and your job requires you to speak on behalf of the silenced. How do you deal with such depressing atmosphere? Does that get into your personal life and affect your everyday activities as ordinary person?

Yes, it could be frustrating; especially when you get absorbed for long, in bleak situations such as Libya. I worked on Libyan case—attempting to project the harrowing stories—every day for about two years. But helping others is deeply rewarding and challenging. When a mother writes me asking to draw her son who is imprisoned in a Saudi jail; when people directly involved in an event are using my arts to tell their stories; when my drawings enter every day in history, the depressing atmosphere reverses. Then I get energized to draw about injustice in a renewed passion.

I can tell you are very industrious and keep wondering how quickly you respond to new developments. On average how many hours do you devote to activism?

I’m always online and in contact with many people around the world. I dedicate approximately half of my day to activism. But in the end my “official” work is activism; my clients are mostly organizations working on this field.

Intevista a cura di Pen Eritrea, sezione in Eritrea di Pen International.

From the website peneritrea.com

Per accedere ai disegni di Gianluca Costantini:

https://www.nuovetracce.org/#section-5df69a3d08f7f

Gianluca Costantini is an activist and artist who for years fought his battles through the drawing. Censored on the web by the Turkish government, he angered many French readers for a short comic about Charlie Hebdo's terrorist story. He actively collaborates with ActionAid, Amnesty, Cesvi, ARCI and Oxfam organizations. His drawings mapped the story of the HRW Film Festival in London, the FIFDH Human Rights Festival in Geneva, the Human Rights Festival of Milan and the International Festival in Ferrara.

Since 2016 she has accompanied the activities of DiEM25 Democracy in Europe Movement 2025, movement founded by Yanis Varoufakis and actively collaborates with the artist Ai Weiwei.

In 2017 he was nominated for the European Citizenship Awards. In 2019 he received the Art and Human Rights award from Amnesty International.

He has published comic stories on "Internationale", "Pagina99", "D la Repubblica", "Narcomafie" and "Corriere della Sera" in Italy, on "LeMan" in Turkey, on "Courrier International" and "Le Monde Diplomatique" in France, on "World War Illustrated" in the United States. He collaborates with the American information portals CNN, Words Without Borders and Muftah Magazine, The New Arab and the Dutch Drawing the Times.

His latest books are Libia for Mondadori, Fedele alla linea, Diario segreto di Pasolini, Pertini fra le nuvole, Arrivederci Berlinguer, Cena con Gramsci, Julian Assange dall’etica hacker a Wikileaks for BeccoGiallo Edizioni and Cattive abitudini, L’ammaestratore di Istanbul e Bronson Drawings for Giuda edizioni, Officina del macello for Eris Edizioni and Le cicatrici tra i miei denti for NdA edizioni.